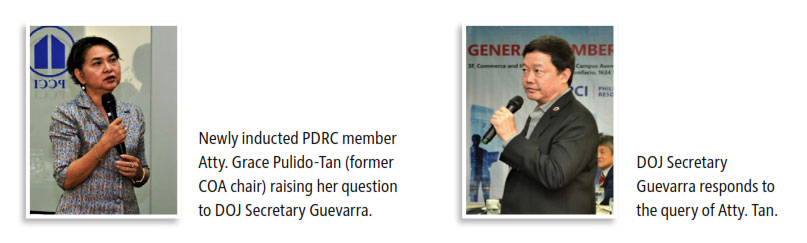

During the open forum at the PDRCI 2018 general membership meeting where he was guest speaker, DOJ Secretar y Menardo I. Guevarra clarified in his reply to a quer y by former Commission and Audit chairman Grace Pulido-Tan that resort to arbitration is deemed written in government construction contracts without any arbitration clause, because this was expressly mandated by the Government Procurement Act (Republic Act No. 9184) and its 2016 Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations.

Secretary Guevarra pointed out, however, that the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission should request an official DOJ Opinion on the matter.

COA review of final awards against the Philippine government

PART 2

Part 1 discussed money claims based on final arbitral awards against the Philippine government. In this issue, the author will discuss the COA’s authority to review final arbitral awards.

COA’s authority to review adjudicated money claims The COA’s power to settle all claims and debts due from the Government applies only to liquidated claims, those determined or readily determinable from vouchers, invoices, and such other papers within reach of accounting of ficers (Euro-Med Laboratories Phil., Inc. v. Prov. of Batangas, 495 SCRA 301 (2006); “Euro-Med”]. In a concurring opinion, then Associate Justice, now Chief Justice, Teresita Leonardo-de Castro explained that before the Government parts with public funds or property, the claim against it must be fixed, definite or settled. Otherwise, the Government may be holding itself liable for unfounded or baseless claims. The power to settle a liability of the Government entails the disbursement of public funds or property, which is subject to stringent rules to safeguard against loss or wastage of such funds or property that are so vital to the delivery of basic public goods and services. Not the least of these rules is Article VI, Section 29(1) of the Constitution, which states that “[n]o money shall be paid out of the Treasury except in pursuance of an appropriation made by law” and §4 of the Government Auditing Code of the Philippines, which also provides that “Government funds or property shall be spent or used solely for public purposes.” [Strategic Alliance Dev’t Corp. v. Radstock Securities, Ltd., 607 SCRA 413, 536 (2009)]

COA’s authority to review adjudicated money claims The COA’s power to settle all claims and debts due from the Government applies only to liquidated claims, those determined or readily determinable from vouchers, invoices, and such other papers within reach of accounting of ficers (Euro-Med Laboratories Phil., Inc. v. Prov. of Batangas, 495 SCRA 301 (2006); “Euro-Med”]. In a concurring opinion, then Associate Justice, now Chief Justice, Teresita Leonardo-de Castro explained that before the Government parts with public funds or property, the claim against it must be fixed, definite or settled. Otherwise, the Government may be holding itself liable for unfounded or baseless claims. The power to settle a liability of the Government entails the disbursement of public funds or property, which is subject to stringent rules to safeguard against loss or wastage of such funds or property that are so vital to the delivery of basic public goods and services. Not the least of these rules is Article VI, Section 29(1) of the Constitution, which states that “[n]o money shall be paid out of the Treasury except in pursuance of an appropriation made by law” and §4 of the Government Auditing Code of the Philippines, which also provides that “Government funds or property shall be spent or used solely for public purposes.” [Strategic Alliance Dev’t Corp. v. Radstock Securities, Ltd., 607 SCRA 413, 536 (2009)]

Once the claim is liquidated, however, the court’s jurisdiction ceases and the COA acquires primar y jurisdiction over the money claim, even if the decision has become final and executor y and a writ of execution has been issued. The allowance or disallowance of adjudicated money claims is for COA to decide, subject only to the remedy of appeal by petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court (NPC DAMA, supra). Trial courts have no authority to direct the immediate withdrawal of garnished funds from the depository banks of the government, and by authorizing the withdrawal of garnished funds, the trial court acts beyond its jurisdiction and all its orders and issuances are void and of no legal effect [Star Special Watchman and Detective Agency v. Puerto Princesa City, 722 SCRA 66 (2000); “Star Special Watchman”]. A money claim against the Government involves compliance with applicable auditing laws and rules on procurement, which matters are not within the usual area of knowledge, experience and expertise of most judges but within the special competence of COA auditors and accountants. Thus, it is proper, out of fidelity to the doctrine of primary jurisdiction, for trial courts to dismiss a complaint for collection of a money claim (Euro-Med, supra).

In the more recent case of Department of Environment and Natural Resources v. United Planners Consultants, Inc., 751 SCRA 389, 409 (2015), the Supreme Court clarified that the primary jurisdiction of COA over money judgments against the government extends to final arbitral awards. A claimant who prevails in the arbitration must first seek the approval of the COA before it can recover its monetary claim against the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, despite finality of the arbitral award confirmed by the Regional Trial Court pursuant to the Special ADR Rules.

COA has no power to modify arbitral awards

However, the COA’s review of a final and executory arbitral award does not allow it to change, amend, modify or reverse a ruling rendered by an arbitral tribunal in favor of a claimant after due proceedings were held. The general jurisdiction of the COA under the Government Auditing Code to “settle all debts or claims of any sort due from … the Government” is limited to the accounting settlement of the adjudicated claim or, as explained in EuroMed, the compliance with applicable auditing laws and rules on procurement. In NPC DAMA, the Supreme Court held that the list of illegally dismissed employees and the computation of their separation benefits were subject to the COA’s validation and audit procedures. As a result, the trial court’s initial computation of P62 billion due to the dismissed employees was reduced to P8.4 billion after COA’s evaluation.

If the COA finds that the money claim is covered by an appropriation and that the claimant is entitled to payment pursuant to the final award, it shall order the respondent to comply with the award. Otherwise, if there is no appropriation to cover the award, it shall direct the respondent to pass an appropriation law or ordinance or other specific statutor y authority [Rallos v. City of Cebu, 704 SCRA 378 (2013)]. In case of failure by respondent to do so, the claimant may compel the enactment of an appropriations law through a petition for mandamus (Star Special Watchman, supra).

The modification of a final and executor y arbitral award also conflicts with the time-honored doctrine of immutability of final judgment, which states that a decision that has acquired finality becomes immutable and unalterable, and may no longer be modified in any respect (Philippine Airlines, Inc. v. Airline Pilots Ass’n of the Phils., G.R. No. 200088, Feb. 26, 2018). Under this rule on immutability of judgments, COA is barred from overturning or amending an unfavorable but final award against a government entity.

In Uy v. Commission on Audit, 328 SCRA 607 (2000), the Supreme Court held that the COA, in the exercise of its broad power to audit, cannot set aside the Merit Systems Protection Board’s final decision requiring Provincial Government of Agusan del Sur to pay the backwages of its illegally dismissed employees. The High Court held that “final judgments may no longer be reviewed or in any way modified directly or indirectly by a higher court, not even by the Supreme Court, much less by any other of ficial, branch or department of Government” (Id., at 617 ).

The current law on arbitration, Republic Act 9285 (2004), the “Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 2004,” adopted the UNCITRAL Model Law of 1985 and its policy of non-intervention on the substantive merits of arbitral awards. In a 1998 opinion, the Supreme Court affirmed that “(a)s a rule, the award of an arbitrator cannot be set aside for mere errors of judgment either as to the law or as to the facts. Courts are without power to amend or overrule merely because of disagreement with matters of law or facts determined by the arbitrators. They will not review the findings of law and fact contained in an award, and will not undertake to substitute their judgment for that of the arbitrators, since any other rule would make an award the commencement, not the end, of litigation. …” [Asset Privatization Trust v. Court of Appeals, 300 SCRA 579, 601-02 (1998)]. This means that an arbitral award is final and binding and a party to an arbitration is precluded from filing an appeal or a petition for certiorari questioning the merits of an arbitral award (Special ADR Rules, Rule 19.7).

In a recent case, the Supreme Court declared itself without jurisdiction to review the merits of an arbitral award: “There is no law granting the judiciary authority to review the merits of an arbitral award. If we were to insist on reviewing the correctness of the award …, it would be tantamount to expanding our jurisdiction without the benefit of legislation. This translates to judicial legislation—a breach of the fundamental principle of separation of powers.” [Freuhauf Electronics Phils. Corp. v. TEAM, 810 SCRA 280, 319 (2016)] Whether or not the arbitral tribunal correctly passed upon the issues is irrelevant. Regardless of the amount of the sum involved in a case, a simple error of law remains a simple error of law. Courts are precluded from revising the award in a particular way, revisiting the tribunal’s findings of fact or conclusions of law, or otherwise encroaching upon the independence of an arbitral tribunal. In other words, simple errors of fact, of law, or of fact and law committed by the arbitral tribunal are not justiciable errors in this jurisdiction (Id.).

If courts, with their broad power of judicial review under the Constitution, cannot amend or modif y final awards in arbitration, then all the more should COA have no such authority since its statutory authority is limited to the audit settlement of money claims.