The Philippine business climate is hampered by major challenges facing the country’s judicial system despite attempts at reforms in recent years. This is the thesis of Arangkada Philippines Forum’s report on the Philippine judicial system in its Fifth Anniversary Assessment as it calls for more intensified reforms.

The Philippine business climate is hampered by major challenges facing the country’s judicial system despite attempts at reforms in recent years. This is the thesis of Arangkada Philippines Forum’s report on the Philippine judicial system in its Fifth Anniversary Assessment as it calls for more intensified reforms.

One of the proposed reforms is to make greater use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) and arbitration to resolve civil disputes out of courts.

Arangkada, a project of the Joint Foreign Chambers of the Philippines, maps out the major problems in the country’s judicial system. Foremost among these are the delays and inefficiencies in the settlement of cases due to clogged court dockets.

Arangkada notes that while the Philippines’ ranking in the Global Competitiveness Report for efficiency of legal settlement has improved from 123rd in the years 200910 to 87th of 140 countries in the years 2015-16, it is still the second lowest among the ASEAN-6. The Supreme Court itself is saddled with 7,000 cases divided among fifteen justices, while the efforts to computerize the court system has not been widely successful in the lower courts.

In its listing of twelve recommendations to address the issues facing the Philippine judiciary, two pertain to the promotion of arbitration and ADR. Arangkada emphasized the importance of making greater use of ADR and arbitration to lessen the number of cases filed in court.

Arangkada reports that there has been consistent substantial progress in this aspect of the reforms for the years 2011 to 2015, which resulted in a significant decline (4.5%) in caseload per judge. Arangkada also lauds the efforts of the Philippine Mediation Center Office as it continues to establish new mediation center units as well as the Philippine Judicial Academy’s training of new judicial stations nationwide for Judicial Dispute Resolution.

In line with these reforms, Arangkada calls for the immediate passage of the new Draft Rules of Civil Procedure (New Rules) which it expects to significantly advance ADR practice in the Philippines. The New Rules has pending review by the Supreme Court since 2014.

Arangkada also recommends the strengthening of international arbitration by ensuring that courts do not reopen the merits of the case when confirming foreign arbitral awards for execution in the Philippines. Arangkada reports that initial steps in this aspect had been taken in 2009 through the issuance of the Special ADR Rules of Court and the implementing rules and regulations of Republic Act No. 9285 (2004) or the ADR Act of 2004.

The Supreme Court has also changed the prevailing jurisprudence by holding that courts can enforce a foreign judgment for execution as long as the foreign judgment and the foreign law under which it was rendered was introduced in evidence by the petitioning party.

PART TWO

The U.S. arbitration debate and why it matters to us

In late October 2015, The New York Times published a series of three articles on complaints against big businesses’ use of arbitration to limit consumers’ ability to sue before regular courts. This article summarizes the report. Part 1 discussed the criticisms of arbitration by consumers. Part 2 reports two recent decisions by California courts that disallowed arbitration as too restrictive.

In the courts, the latest affront comes in the decision in Mohammed et al. v. Uber Technologies, Inc., N.D. Cal. June 9, 2015, which struck down employment arbitration agreements for being procedurally and substantially unconscionable.

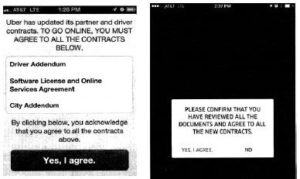

Mohammed involved a putative class, individual and representative claims under the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act, the California Investigative Consumer Report Agencies Act, the California Private Attorneys General Act (PAGA), and other laws filed by Mohammed and Gilette, respectively, against Uber. Uber moved to dismiss the cases on the ground that the parties allegedly agreed to arbitration in two sets of arbitration contracts: the 2013 and the 2014 Agreement, which required the plaintiffs to click two boxes to show their assent. These agreements contained a delegation clause that delegated the authority to determine its enforceability to an arbitrator, and not the court.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, however, ruled that while the parties did enter into the contracts, the delegation clauses found in both 2013 and 2014 Agreements were nevertheless unenforceable since they failed to meet the “clear and unmistakable” test. Particularly, a forum-selection clause in the agreements stated that “any disputes, actions, claims or causes of action arising out of or in connection with this Agreement or the Uber Service or Software shall be subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the state and federal courts located in the City and County of San Francisco, California.”

Moreover, the court ruled that even if the delegation clauses were clear and unmistakable, they were themselves unconscionable, and thus unenforceable, under California law. Among others, the court found the agreements oppressive under California law because of their fee splitting

Moreover, the court ruled that even if the delegation clauses were clear and unmistakable, they were themselves unconscionable, and thus unenforceable, under California law. Among others, the court found the agreements oppressive under California law because of their fee splitting

provisions, in which claimants are required to pay significant forum fees just to initiate arbitration and determine arbitrability.

The court also pointed out that the agreements are in the nature of an “adhesion contract” that deprived the plaintiffs of the opportunity to bargain. The agreements were likewise difficult to access and the delegation and arbitration provisions were not highlighted in a way to make them conspicuous.

Uber argued that the 2014 Agreement, at least, was purely voluntary because a driver could—in principle—opt out of the arbitration program. Citing Gentry v. Superior Court, 42 Cal. 4th 443, 469 [2007], a California Supreme Court decision, the court held that the opt-out option itself could not rescue the agreement since Uber still failed to conspicuously disclose “the disadvantageous terms of the arbitration agreement” (i.e., payment of considerable forum fees) in connection with the opt-out provision.

Aside from being procedurally unconscionable, the court also found both agreements substantively unconscionable and unenforceable because they purport to waive plaintiffs’ right to bring representative PAGA claims in any forum. Under PAGA, “an ‘aggrieved employee’ may bring a civil action personally and on behalf of other current or former employees to recover civil penalties for Labor Code violations.” Stated otherwise, it functions as a substitute for an action brought by the government itself.

In the recent case of Iskanian v. CLS Transp. L.A., LLC, 59 Cal. 4th 348, 173 Cal. Rptr. 3d 289, 327 P.3d 129 (2014), the California Supreme Court categorically held that “an agreement by employees to waive their right to bring a PAGA action serves to disable one of the primary mechanisms for enforcing the Labor Code. Because such an agreement has as its object indirectly to exempt the employer from responsibility for its own violation of law it is against public policy and may not be enforced.”

In addition to the PAGA waiver, the court also found both agreements substantially unconscionable because they: (a) contained broad confidentiality terms, (b) carved out Uber’s right to go to court to enforce intellectual property claims, and (c) allowed Uber to unilaterally modify the terms of the contract without notice to drivers.

Because of the unenforceability and procedural and substantive unconscionability of the agreements, the court ruled that Uber could not compel plaintiffs to arbitration.

While this decision may be limited by its reliance on California law, Louis F. Burke, New York, N.Y. cochair of the Section of Litigation’s Alternative Dispute Resolution Committee of the American Bar Association, considers it “a good example of what we need to think about, even if it may not be the law of some other jurisdiction.”

This recent decision in Mohammed, like the Times report, highlight a growing concern that resort to arbitration results in the “whole-scale privatization of the justice system” that deprives persons of their right to their day in court.