PDRCI joined the Philippine Institute of Arbitrators and the Philippine Institute of Construction Arbitrators and Mediators in holding an international conference on alternative dispute resolution on November 8 to 9, 2012 in Manila. The two-day event, attended by leading ADR experts, was held at the Hotel InterContinental in Makati City.

PDRCI President Victor P. Lazatin welcomed the delegates with his message that the conference theme, “Sharing ADR best practices,” adheres closely to PDRCI’s philosophy that “a candle does not lose any of its light by lighting another candle.” “Knowledge that is shared,” Mr. Lazatin stressed, “does not diminish but rather multiplies as it is passed on.” The was facilitated by PDRCI Trustees and members such as Dean Custodio O. Parlade, Eduardo Ceniza, Arthur Autea, Ricardo P.G. Ongkiko, Gwen B. Grecia-De Vera, and Patricia Ann T. Prodigalidad. Jose Martin R. Tensuan acted as master of ceremonies.

One of the highlights of the conference was Haig Oghigian’s presentation of the International Bar Association (IBA) guidelines on conflicts of interest in international arbitration._Mr. Oghigian, a member of Baker & McKenzie Tokyo and the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb), delivered his lecture through PDRCI Trustee and Baker & McKenzie Manila member Donemark Calimon. He said that even though laws and arbitration rules provide some disclosure standards, there is a lack of detail in their guidance and uniformity in their application. As a result, he added, members of the international arbitration community quite often apply different standards in making decisions concerning disclosure, objections and challenges.

To address this issue, Mr. Oghigian said that the IBA created colorcoded guidelines on conflicts of interest in international arbitration known as the Red, Orange and Green Lists. The Red Non-Waivable and Waivable Lists identify situations that raise justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence. The Orange List reflects situations where the arbitrator has a duty to disclose. The Green List identify situations where the arbitrator has no duty to disclose. He emphasized that the Guidelines are not legal provisions and that they do not override any applicable national law or arbitral rules chosen by the parties.

Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) chief executive officer Minn Naing Oo gave a survey of developments on judicial construction of the public policy exception in the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards in Asia.

Mr. Oo noted that Singaporean courts consistently construed the public policy exception narrowly and aided the The Philippine ADR Review is a publication of the Philippine Dispute Resolution Center, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the newsletter may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the authors. Roberto N. Dio, Editor Shirley Alinea, Donemark Calimon, Ramon Samson, Contributors Arveen N. Agunday, Juan Paolo E. Colet, enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. He said that Indonesian courts adopted a broad and vague construction of public policy exception. He added that recent decisions in some jurisdictions have contributed to the confusion. Mr. Oo said that Indian courts have been “notorious” in expanding the scope of the public policy exception. However, he expressed the hope that Indian courts would adopt a more pro-arbitration approach in construing the scope of the exception. He said that overall, there is a slow but sure movement towards a non-interventionist approach in enforcing arbitral awards.

Philippines Public-Private Partnerhip Center’s Romell Antonio O. Cuenca, who is the Center’s Director of Legal Service, introduced the services of the PPP Center to the delegates. He informed the delegates that amendments to the Philippine Build-Operate-Transfer Law are now under congressional deliberation.

The delegates included representatives from the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre, Hong Kong Institute of Arbitrators, and other arbitration institutes. Other participants were members of the business sector and academia.

Accreditation guidelines for ADR provider organizations and training standards for ADR practitioners

On August 17, 2012, the Office for cAlternative Dispute Resolution (OADR), through the Department of Justice, promulgated Department Circular No. 49 (Adopting Accreditation Guidelines for Alternative Dispute Resolution Provider Organizations and Training Standards for Alternative Dispute Resolution Practitioners).

The Guidelines were enacted pursuant to Section 50 of the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 2004 (“ADR Act”), which empowered the OADR to formulate training standards for and to certify the professional training of ADR practitioners and service providers.

Accreditation, in general

As a rule, the Guidelines mandate accreditation only for ADR practitioners and ADR provider organizations (“APO”) that offer their services to government agencies or in partnership with said agencies.

A private APO, such as PDRCI, is a private sector APO that offers ADR training programs or dispute resolution services to the general public, to government agencies, or in partnership with said agencies. A public APO is a government agency that offers ADR training programs or dispute resolution services within that agency, to the general public, to other government agencies, or in partnership with said other agencies

Private APOs offering ADR services to government agencies or in partnership with said agencies are required to secure OADR accreditation. However, accreditation is voluntary for private APOs that offer services to the general public, but not to government agencies or in partnership with government agencies.

The ADR programs of public APOs—except those of the Constitutional Commissions (Commission on Audit, Commission on Elections, and Civil Service Commission), the Philippine Congress, the Supreme Court and its subordinate agencies and all lower courts, and the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission, as well as ADR programs under the Labor Code and the Katarungang Pambarangay Law—shall also be accredited by the OADR.

ADR practitioners, or those individuals acting as a mediator, conciliator, arbitrator, neutral evaluator, or exercising similar functions in any ADR system, offering ADR services to government agencies or in partnership with said agencies are likewise required to secure OADR accreditation. For ADR practitioners offering services to the general public but not to government agencies or in partnership with government agencies, OADR accreditation is voluntary.

Chapter I, Title I of the Guidelines applies to ADR practitioners trained by accredited APOs, while Title II covers the accreditation of APO practitioners trained by non-accredited APOs, ADR centers or institutions.

Requirements for accreditation

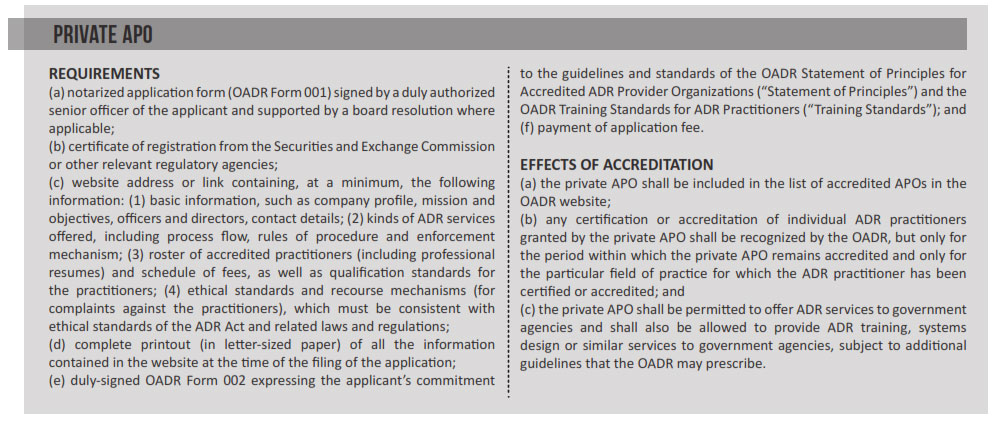

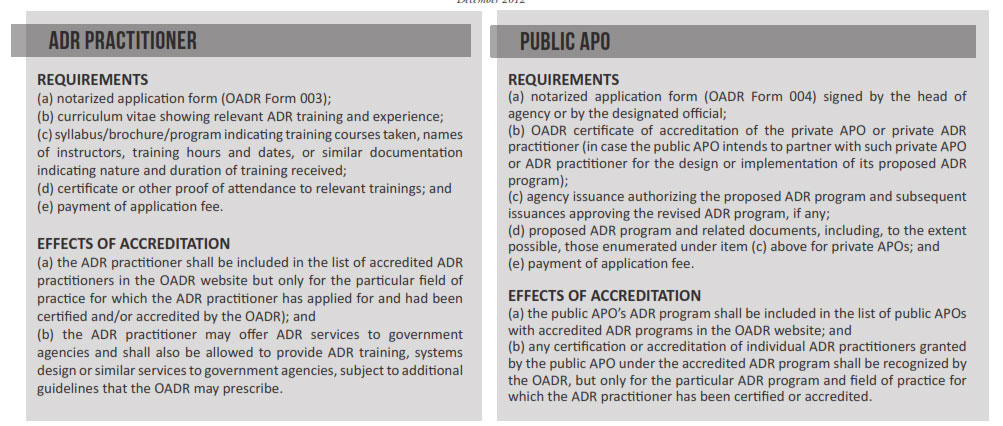

The following table shows the requirements for and the effects of accreditation of private APOs, public APOs, and ADR practitioners:

Applications for accreditation submitted by an APO or ADR practitioner will be initially evaluated by the OADR for completeness or defects, in

which case the applicant will be directed to make the corresponding corrections or submit additional documents.

Accreditation of ADR training program

Private and public APOs as well as ADR practitioners who intend to offer ADR training shall also submit their proposed training program to the OADR for approval. The proposed training program (including the faculty resumes/curriculum vitae and training materials/module) shall be submitted to the OADR at least one month prior to the intended training date. The OADR may require changes to the training program in accordance with the Guidelines and may monitor the training program by sending a representative. Any substantial deviation from the approved program without written approval of the OADR may be a ground for revocation of accreditation of the provider of the training program.

Term of accreditation

Once an APO or ADR practitioner is accredited by the OADR, the accreditation shall be valid for two years, subject to renewal upon submission of a new application form, payment of the required fees, and compliance with additional requirements that may be set by the OADR.

Those who were accredited as ADR practitioners under existing government ADR programs prior to the Guidelines will be recognized as accredited ADR practitioners for one year from the effectivity of the Guidelines, after which they must comply with the accreditation requirements under the Guidelines.

Monitoring by the OADR

The OADR shall monitor the compliance by accredited APOs with their commitments to the guidelines and principles provided under the Guidelines, as well as the OADR Statement of Principles and the OADR Training Standards.

Revocation of accreditation

Upon complaint of any interested party or motu proprio, the OADR may revoke any accreditation upon a finding of (a) material violation of any provision of the OADR Statement of Principles or the OADR Training Standards; (b) failure to maintain the website required under the Guidelines, or its material alteration in such a way that the private APO adopts ethical, professional, practice, legal or administrative standards significantly lower than those initially represented in the original website; or (c) any other violation or circumstance of a similar nature and/or

analogous to items (a) and (b). The OADR shall prepare a separate guideline outlining the procedure for resolving complaints against accredited entities.

Minimum ADR training standards

Under the Guidelines, an ADR training program shall comply with the following minimum standards:

- a detailed statement of the training objectives and expected outcome in terms of knowledge to be imparted and skills to be taught:

- the program must directly meet the objectives and expected outcomes of the training program • the lecturers, trainors and facilitators either have advanced training in ADR or worexperience of at least three years in the specific ea/s covered by the assigned topic

- it must consist of at least 24 hours of lecturand/or coursework and a minimum of 16 hours of simulations, practical exercises and/or skills training

- it shall cover the following areas: (1) discussion of applicable laws, administrative and executive issuances on ADR; (2) ADR theory and concepts, depending on whether the course covered is mediation or arbitration; (3) subject-matter content, which shall include materials applying ADR theory and concepts to the typical types of ADR disputes; and (4) practical exercises, role plays, simulations or similar skills-based training.

The participants in the training program shall undergo either a written or skills assessment to test their understanding of the concepts and skills imparted. In case the training covers

mediation, conciliation or any other consensusbased process, skills assessment is mandatory.

While an apprenticeship or mentoring program is not required, the Guidelines strongly encourages each APO to adopt this as part of their continuing education/training for newly accredited

practitioners. The OADR will issue operational guidelines for the implementation of the Guidelines within 90 days from its effectivity.