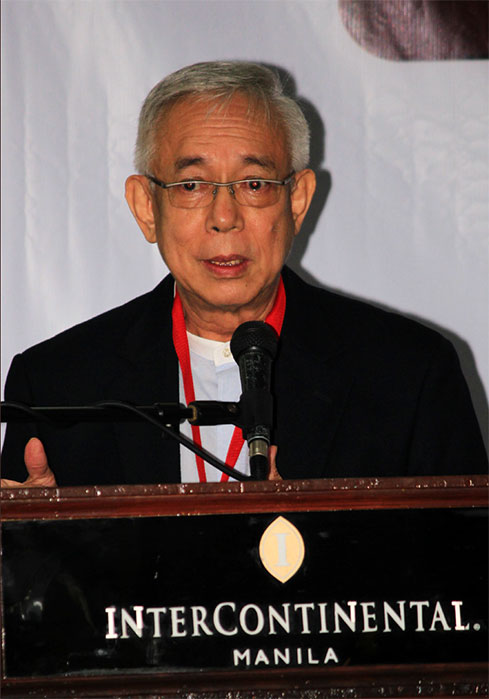

Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC), the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, has admitted Engr. Salvador P. Castro, Jr. as one of its Affiliate Members at its General Assembly Meeting on September 12, 2012 in Seoul, Korea. Engr. Castro is a Trustee of PDRCI and head of its Mediation Committee.

Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC), the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, has admitted Engr. Salvador P. Castro, Jr. as one of its Affiliate Members at its General Assembly Meeting on September 12, 2012 in Seoul, Korea. Engr. Castro is a Trustee of PDRCI and head of its Mediation Committee.

A civil engineer by profession, he is the Chairman and President of SPCastro, Inc., a project management firm with operations in the Philippines and the United Arab Emirates. He has been a FIDIC Accredited Trainer since 2011.

FIDIC is a global representative for the consulting engineering industry, promoting the business interests of firms supplying technology-based intellectual services for built and natural environments alike. Founded in 1913, its members are mainly national associations of consulting engineers. It is charged with promoting and implementing the consulting engineering industry’s strategic goals on behalf of its member associations as well as dissemination of information and resources of interest to its members.

FIDIC publishes international standard forms of contracts for works and for clients, consultants, sub-consultants, joint ventures and representatives, together with related materials such as standard prequalification forms.

FIDIC is well known for its suite of standard form Conditions of Contract for the worldwide construction industry, particularly in the context of higher value international construction projects, and is endorsed by many multilateral development banks.

Membership in FIDIC is classified into three: Member Associations, Affiliate Members and Associate Members. FIDIC currently has 94 Member Associations and Associates, composed of corporations, professional partnerships and associations. Only one Member Association is chosen per country.

In the Philippines, the only FIDIC Member Association is the Council of Engineering Consultants of the Philippines (CECOPHIL), which was established in October 1976 and is considered the largest engineering consulting association in the country.

FIDIC has 28 Affiliate Members consisting of 22 company-based and six individual members. Of the six individual members, Engr. Castro is the only FIDIC Affiliate Member from Asia.

Prior to becoming FIDIC Affiliate Members, applicants must undergo rigorous training, and must pass a series of FIDIC examinations. Once qualified, their applications must then be approved and ratified by the FIDIC Executive Committee at a FIDIC General Assembly. As one of the new FIDIC Affiliate Members, Engr. Castro has been invited to attend the next FIDIC Centenary Conference in Barcelona, Spain.

The concept of "public policy" in the enforcement of arbitral awards

We learned from the presentation of Minn Naing Oo that the term “public policy” as used in the enforcement of an arbitral award does not have a uniform meaning. Different countries have different notions of what public policy is. That makes public policy a tough subject to discuss.

We learned from the presentation of Minn Naing Oo that the term “public policy” as used in the enforcement of an arbitral award does not have a uniform meaning. Different countries have different notions of what public policy is. That makes public policy a tough subject to discuss.

Whether in Asia or elsewhere, the meaning of public policy in the enforcement stage of the arbitral award can be broad or narrow. At the outset, let me state that according to the editors of the “Interim Report on Public Policy as a Bar to Enforcement of International Arbitral Awards” published by the International Law Association in connection with its London Conference 2000, it is “notoriously difficult” to provide a precise definition of public policy.

In one old English case, Egerton v. Brownlow, [1853] 4 HLV1, which provided the germ of what later on will become the narrow meaning or concept of public policy in the context of enforcement of arbitral awards, the English Court of Appeals described— but did not define— public policy as “that principle of law which holds that no subject can lawfully do that which has a tendency to be injurious to the public good, or against public good.” In another English case of more recent vintage, Deutsche Schachtbau-und v. Ras Al Khaimah National Oil, [1987] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 246, 254, the Court explained public policy in the context of the enforcement of an arbitral award in this language:

Considerations of public policy can never be exhaustively defined, but they should be approached with extreme caution. … It has to be shown that there is some element of illegality or that the enforcement of the award would be clearly injurious to the public good or, possibly, that enforcement would be offensive to the ordinary reasonable and fully informed members of the public on

whose behalf the powers of the State are exercised.

The definition of public policy most often quoted is that of U.S. Circuit Court Judge Joseph Smith in Parsons & Whittemore Overses Co., Inc. V. Societe Generale de L’Industrie de papier RAKTA and bank of America, 508 F. 2nd 969 (2nd Cir., 1974), in which he held that enforcement of a foreign arbitral award may be denied on public policy grounds “only where enforcement would violate the forum’s most basic notions of morality and justice.”

Revolving around this terse and narrow definition of public policy, Singapore and Hong Kong Courts have held that public policy should only operate in instances where the upholding of an arbitral award “would shock the conscience” or is “clearly injurious to the public good” or “wholly offensive to the ordinary reasonable and fully informed member of the public.”

The New York Convention of 1958

Article V2(b) of the New York Convention provides that “recognition and enforcement of an arbitral award may also be refused if the competent authority in the country where recognition and enforcement is sought finds that … the recognition and enforcement of the award would be contrary to the public policy of that country.” The way the provision was drafted seems to indicate that the drafters of the 1958 New York Convention did not attempt to harmonize public policy or to establish a common international standard.

UNCITRAL Model Law

The 1985 UNCITRAL Model Law owes its origins to a request made in 1977 by the Asian-African Legal Consultative Committee for a review of the operations of the New York Convention. The Committee maintained that there was an apparent lack of uniformity in the approach of national courts to the enforcement of awards. The Secretary-General of UNCITRAL concluded that harmonization of the enforcement practices of States, and the judicial control of the procedure, could be achieve more effectively by the promulgation of a model or uniform law rather than by any attempt to revise the New York Convention.

The final text of the Model law was adopted in 1985. The Model Law includes “public policy” as a ground for setting aside an award by the courts in the seat of arbitration (Art. 34) and as a ground for refusing recognition and enforcement of a foreign award (Art. 36), in essence echoing Article V2(b) of the New York Convention. Unfortunately, the Model Law does not define “public policy.” [Interim Report on Public Policy as a Bar to Enforcement of International Arbitral Awards, International Law Association, London Conference (2000), p. 9].

There is a Philippine case mentioned by Mr. Minn, Luzon Hydro Corporation v. Hon. Baybay and Trans-Filed Philippines, CA-G.R. SP No. 93418, November 29, 2006, decided by the Philippine Court of Appeals, which involved an ICC arbitration seated in Singapore. The arbitrator awarded cost to the claimant by applying the familiar rule “cost follows the event.” When the award was enforced in the Philippines, the Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals set aside the award on the ground that it violated public policy because there was no law in the Philippines authorizing the assessment of cost of litigation on a losing party. The appellate court said that to make a bona fide litigant bear the cost of the other party was contrary to public policy.

For the sake of academic discussion and with due respect to the Court of Appeals, I wish to point out two errors in this decision.

First, it is not true that there is no law in the Philippine that authorizes a court to assess cost on the losing party. Rule 142, Section 1 of the Revised Rules of Court provide that cost may be assessed against the losing party “as a matter of course.” However, the court is given discretion not to award cost in favor of the successful party depending on the circumstances of the case. Hence, it is not correct that there is no law that authorizes the assessment of cost on the losing litigant. Also, the fact that the court is given discretion to award or not to award cost can only mean that there is a public policy on cost.

The second error is the fact that the Court of Appeals had no jurisdiction to set aside a foreign arbitral award. The Philippine court, being a court of secondary jurisdiction, can only refuse recognition and enforcement of a foreign arbitral award on the limited grounds provided in Article V of the New York Convention, but certainly it cannot set aside a foreign arbitral award.

In another case decided by the Philippine Supreme Court, Korea Technologies v. Hon. Alberto Lerma, G. R. No. 143581, January 07, 2008, it stated in an obiter dictum that a Regional Trial Court, pursuant to Article 34(2) of the Model Law, has jurisdiction to set aside a foreign arbitral award. However, when a foreign arbitral award is sought to be enforced in the Philippines, a Philippine court, being a court of secondary jurisdiction, can only refuse to recognize and enforce such foreign arbitral award on the limited ground provided in Article V of the New York Convention. Only the proper court of the place of arbitration, as the court of primary jurisdiction, has the power to set aside the award under the limited grounds provided in Article 34(2) of the Model Law.

Errors like these are bound to occur as our courts struggle to learn the relevant nuances of international arbitration and the processes envisaged by the New York Convention, which was ratified by the Philippine Senate in 1967, and the Model Law, which was adopted as the Philippine law on international arbitration in 2004 by Republic Act 9285.

In the Asia-Pacific region significant measures have been taken to promote arbitration as a form of alternative dispute resolution, at least in terms of legislation. In some countries, the judiciary is still struggling to come to terms with their role in the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. One problem lies in the judicial interpretation of modern legislation and its resultant conflict with old case law. Another problem appears to be the continuing anxiety about arbitration. While some of it may be attributed to a lack of familiarity with the process and relevant international consensus, the rest appears to be founded on misplaced judicial parochialism.

With Singapore and Hong Kong in the forefront, international commercial arbitration in Asia has come of age. Some arbitral institutions in Asia, such as the Singapore International Arbitration Centre and the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre have risen to the stature of leading interntional arbitral institutions. It is the author’s hope, expressed with a good measure of confidence, that the other arbitral institutions in the region, including our very own PDRCI, will follow the lead of Singapore and Hong Kong and in good time establish themselves in their rightful place in this part of the world.