Among the changes being proposed in the new Corporation Code by the Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is the adoption of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) as a mode of resolving intra-corporate disputes.

Among the changes being proposed in the new Corporation Code by the Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is the adoption of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) as a mode of resolving intra-corporate disputes.

SEC Chair Teresita J. Herbosa, who spoke at PDRC’s annual general meeting last July 15, 2016, described how the Commission will roll out its mediation program with the training of new mediators. Once the mediation program is in place, the SEC will pursue arbitration as an alternative mode of resolving intra-corporate disputes.

At present, intra-corporate disputes are heard by Regional Trial Courts under a special rules of procedure on intra-corporate disputes. Although the procedure is supposed to be summary, proceedings can be protracted and cases can drag for years.

The SEC aims to address this by giving the parties an opportunity to resolve their disputes privately through arbitration. The parties may select from a list of arbitrators accredited by the SEC, such as those from PDRC. The SEC Chair, who is a member of PDRC before she assumed her office, spoke highly of the efficacy of arbitration as an ADR mode. She said that one of the provisions in the proposed new Corporation Code to be submitted to the 17th Congress will encourage corporations to provide in the articles of incorporation and by-law stipulations the use of ADR in resolving intra-corporate disputes.

In addition to ADR, the changes in the new Corporation Code include provisions on ease of doing business, corporate and stockholder protection, corporate civil responsibility, and policy and regulation.

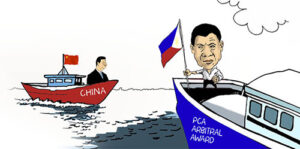

Philippines vs. china: We won! So, what now?

This is a quick take on the maritime entitlement issues in the arbitration initiated by the Philippines against China. This is culled from the awards on jurisdiction and on the merits, opinions by observers, news reports, and the announced position of the parties as well as interested third parties such as the United States of America (U.S.).

This is a quick take on the maritime entitlement issues in the arbitration initiated by the Philippines against China. This is culled from the awards on jurisdiction and on the merits, opinions by observers, news reports, and the announced position of the parties as well as interested third parties such as the United States of America (U.S.).

On 12 July 2016 the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) released the Final Award issued by the ad hoc Arbitral Tribunal constituted under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS).

There was really nothing new in the ruling such that the result was predictable. On the maritime entitlement disputes and in substance, in so many words the Tribunal merely applied UNCLOS principles on the dispute. Thus:

1. Ownership of the sea (territorial sea) and maritime entitlements (the exclusive economic zone or EEZ and continental shelf) are attached to the land. To be precise, the Award said that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources in excess of the rights provided by UNCLOS, within the sea areas falling within the “nine-dash line.” So there went China’s nine-dash-line claim.

2. In the Award none of the land formations in the South China Sea was considered an “island.” A few were declared as reefs (low tide elevations or sunken banks). The rest were declared “rocks” (high tide elevations).

An “island” is a land formation capable of sustaining habitual and economic human life. It is entitled not only to a twelve-mile territorial sea but also to an exclusive economic zone or EEZ and a continental shelf. It can be acquired.

A “rock” is a land formation that is above water at high tide. It is entitled to a twelve-mile territorial sea but not to an EEZ much less a continental shelf. It can also be acquired.

A reef is a land formation that is below water, or below water at high tide. It is not entitled to anything, is considered part of the high seas and can not be acquired, but it is considered included in the EEZ or continental shelf of the nearest littoral states.

So there went China’s claim of ownership over, and its occupation and development of, some reefs. And there went China’s possible claims of maritime entitlements as to the other land formations.

Note that, by extension, all claimants were affected by the ruling. The features that they administer are either “rocks” or reefs, but not islands.

3. Developments in the land formations will not change their nature. A “rock” remains a “rock” while a reef remains a reef.

The Award was almost a grand slam, in that it upheld almost all of the maritime entitlement submissions (and other submissions as well) of the Philippines. More so because Reed Bank, Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal were declared to be within the country’s presumptive EEZ and continental shelf.

Before we rejoice

Before we rejoice, however, we should take note of the following:

1. There was no decision regarding the ownership of any of the disputed islands or “rocks.” At least, however, the reefs in the West Philippine Sea were declared parts of the sea and therefore part of the Philippine EEZ/continental shelf.

2. Upon implied request of the Philippines, the land formations in Scarborough Shoal were declared “rocks”

that could generate a territorial sea but not anything else . The Philippines won on this point, except that China claims the “rocks” and it is at present in control of those “rocks.” With the Award, China’s garrison and forces can remain in Scarborough Shoal and, possibly, China can develop the “rocks” as well.

While the Award made clear that traditional fishing rights are to be respected, still it would be a rather complicated affair to fish in the lagoon without straying into the twelvemile territorial sea of the “rocks” in Scarborough Shoal.

3. While it may be that China’s nine-dash-line claim was knocked out, still there are overlapping claims over the West Philippine Sea that remain. No decision was made on such claims.

4. The arbitration is both case- and parties-specific. The separate awards on jurisdiction and on the merits stand alone. So, an arbitration between different parties and arbitrators involving the same issues and set of facts may end with different results. The award is, in theory at least, only binding on the parties. Note that the Award stated that the ruling on China’s nine-dash-line is only as between China and the Philippines.

5. Taiwan is not a party to the arbitration. It can not be sued under UNCLOS for the simple reason that it is not a signatory. It’s main claim, called the eleven-dash line, is even more expansive than that of China. Taiwan’s problem is that it is not generally considered a country. 6. The Philippines, in harping on the so-called “rule of law” and “rules-based approach” to resolve the dispute, was focused on the substantive merits of the dispute. China, who was also invoking the rule of law, was focused on the procedure, that is, issues involving jurisdiction, arbitrator partiality and appointing authority partiality and independence as well as possible prejudgment. These issues are expected to linger with the Award.

It is noticeable that those issues are grounds to vacate an arbitral award.

7. The publicly announced positions of the United States are (a) it is adopting a hands-off policy on the dispute, but (b) it will enforce the freedom of navigation and the right of overflights in the maritime area as far as allowed by international law.

So, we can expect the U.S. to engage in “cherry picking.” It will make use of the portions of the Award limiting China’s putative claims on the South China Sea and just pay lip service to the rest. Never mind if the arbitration was both case- and parties-specific.

Other interested powers aligned with the U.S. are expected to follow the same line.

On this point, the disputed islands, those administered by the Philippines included, as well as disputes involving the Philippines’ presumptive EEZ and continental shelf are not covered by the U.S. Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty. The possible exception is the Philippine Navy vessel BRP Sierra Madre, intentionally grounded on Ayungin Shoal by the Philippines and said to be occupied by a few soldiers and rats, which may be considered a “Philippine vessel.”

Parenthetically, the U.S., a non-claimant who nevertheless conducts police actions in the maritime zone, cannot be sued under UNCLOS because it is not a signatory. It also can not be sued in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) because, when sued by Nicaragua, the U.S. did not only refuse to participate but it also withdrew from the mandatory jurisdiction of the ICJ.

There are opinions that the U.S. was the real big winner in the arbitration and that it used the Philippines as the pivot to advance it’s – the U.S.’s – interests.

8. Accordingly, the Philippines is alone and has to fend for itself on its issues of concern, namely the ownership of the islands it claims and/or administers, fishing rights, and the right to exploit resources in the West Philippine Sea.

9. China is not expected to honor the award.

10. In state-to-state arbitration there is no enforcement mechanism. So, the “winner” has to rely on the voluntary compliance by the “loser.”

So, what now?

1. It seems that there is nothing in the Award that disturbs the status quo, unless and until either or both parties, or maybe a third party like the U.S., makes a move.

There is no need for the President to jet ski to Scarborough Shoal. Its premise is that the tribunal would declare that the Philippines owned the shoal, which did not happen.

The Scarborough ruling may instead potentially cause domestic problems. How will the Philippine Government explain to the fishermen that the declaration of the features in Scarborough Shoal as rocks was upon its request and that, as a result, there is now no ground to drive the Chinese away?

So, if at all, any provocative action would come from the U.S. (or the other powers like Japan) in carrying out its Freedom of Navigation and Overflights Operation (FONOP).

2. According to Gary B. Born, “In practice, the principal mechanism for enforcement of state-to-state arbitral awards has been diplomatic persuasion and countermeasures.” Obviously the Philippines does not have the capacity to employ counter-measures.

3 A friend suggested that the Philippines enter into service contracts with other powers. Then they will enforce the Award with respect to the Philippine right to resources within its EEZ. But would the other powers be willing to do so considering the possible consequences? And would it be an advisable option for the Philippines ? 3. An alternative posture, which is to internationally isolate China, may be wishful thinking. Other powers, notably the U.S. (several times at that), France, Japan and Russia have refused to honor international awards and decisions. Sure, they suffered criticism, but none of them were isolated. Even if on those disputes there were no jurisdictional and other procedural issues.

Besides, can we reasonably believe that, apart from lip service, other countries would actively help the Philippines enforce its fishing rights and right to exploit maritime resources within the maritime zone?

As for freedom of navigation and overflight over the zone, all that China has to do is to proceed as usual. Thus far nobody other than the U.S. had interposed any complaint. It is up to the U.S. if it wants to challenge and provoke China by sailing well within the twelve-mile limit of the artificial islands administered by China or by flying over them.

4. Julian Ku, the Maurice A. Deane Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at Hofstra University School of Law, suggested that the Philippines invite (he used the word “dare”) China to elevate the jurisdictional issue (and perhaps the other procedural issues – insertion mine) to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). This could be done if China were to give its consent so that the issue would be laid to rest one way or the other. China would also be in a more friendly tribunal. But that would only prolong the agony.

Besides, I don’t believe that the Duterte administration would be inclined to do that. To do so would be at odds with its pragmatic approach and would place the current administration in the same position as the Aquino administration, the consequence being that the relationship between the two countries would again be “toxic”.

As for China, it would most likely not agree to the proposal. Julian Ku, by the way, subscribes to the view that the tribunal may have no jurisdiction.

5. So, it has to be diplomatic persuasion, which could be a euphemism for negotiation. It seems incongruous that after rejecting negotiation, the Philippines at the end of the day has to go back to negotiation.

Except that now, with the Award, the issues have become more complicated. The declaration that the Philippines owns the maritime resources in the West Philippine Sea effectively tied the hands of the present government.

6. There are arguments that the Philippines should not negotiate because of the disparity in the bargaining strength of the parties. Moreover, China’s posture is seemingly “What is ours is ours, what is in dispute we share.” The problem here is that all Philippine claims are in dispute. If the Philippines would not negotiate, then what is the viable alternative?

7. If the parties were to negotiate and succeed, then the likelihood is that the agreement would begin with words saying that the parties acknowledge that the matter is in dispute, followed by motherhood statements about their desire to peacefully resolve the dispute and remain friends because they are neighbors. In the meantime, for the mutual benefit of the parties, they can agree on temporar y arrangements, which may end as permanent.

China could not reasonably be expected to agree to even a hint that the matter is not in dispute as it has already been settled in favor of the Philippines. The Philippines could not reasonably be expected to agree to even a hint that the matter is still in dispute because the arbitral award had already ruled on the matter.

8. The present administration seems to have a pragmatic approach: let the parties share in the benefits. China would have to spend for it, as the Philippines does not have the capacity and in addition China can help the Philippines, say in building a railway system from the farthest point of Luzon to the farthest point of Mindanao, or building airports and other infrastructures.

But that approach would likely result to domestic problems and accusations of a sell-out, as well as problems on how to disentangle complex legal knots to make any agreement legally workable, at least on the Philippine side. Besides, not all problems could be resolved bilaterally. Those where other claimants are involved would necessarily require a multilateral approach.

Anyway, there are indications that the Duterte administration would be playing a balancing act between the U. S. and China and, in the process, get benefits from both. But this would not really solve the problem.

9. Chas Freeman, a former U.S. diplomat, characterized the Award as a tactical victory for the Philippines and a strategic defeat for international law. According to him, the decision left the issue in the condition where it can only be resolved by the use of force. There is no diplomatic process underway to settle the claims, and now there is no longer a legal process.

10. One thing seems to be certain. There is no viable solution in sight in the near or even the far future. We are back to the question in the title. We won! So, what now? In reply, I will end this piece by paraphrasing the statement of an attendee in one of my pre-Award Mandatory Continuing Legal Education lectures. Substantially he said: one day the Philippines would be strong, economically and militarily. It can then assert and defend itself. If only the Filipino people would elect leaders who are both competent and not corrupt.