At its annual general meeting on December 15, 2014 at its principal office, the Philippine Dispute Resolution Center, Inc. (PDRCI) unanimously passed two changes to its By-Laws.

The first amendment defined “members” in Art. III, Sec. 1 of the By-Laws as consisting of (a) the Trustees, (b) the founding members named in the Articles of Incorporation, unless otherwise removed as a member, deceased or otherwise permanently incapacitated, and (c) such other members admitted from time to time, by a ¾ vote of the members of the Board of Trustees, and who have maintained their membership status by regularly paying the dues assessed by the Center and by attending, in person or by proxy, the last two general membership meetings of the Center that preceded the meeting for which the membership status is to be determined.

The amendment also authorized the Board of Trustees to admit honorary members and officers who shall have no voting rights and no responsibility for the operations of the Center.

The amendment was introduced to prevent a failure of quorum during membership meetings due to the large number of members in the PDRCI roster.

The second amendment in Art. VII, Sec. 8 of the By-Laws provided for the appointment by the Board of Trustees of an Executive Director to assist the Secretary General on a fulltime or part-time basis and with such salary and other emoluments as the Board may fix.

The amendment was introduced to allow a full-time executive director to be appointed by the Center.

Philippine experience in commercial arbitration

Note: This paper was read by Francisco D. Pabilla, Jr., Assistant Secretary General of PDRCI, on behalf of the author at the tenth anniversary celebration of the Office of Alternative Dispute Resolution (OADR).

Use of commercial arbitration in Philippine business

In 2013, major international arbitration centers reported an “unprecedented increase” in the number of commercial disputes referred to them, with the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) reporting a new high of 301 cases, up by 10% from the previous year and breaking its 2009 record of 285 cases, and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) in Paris receiving 767 Requests for Arbitration in 2013, up from 757 the previous year.

Regional arbitration centers in Singapore and Hong Kong reported similar increases for 2013. The Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) handled 259 new cases, up from 235 in 2012, while the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) reported 260 new arbitrations, an increase of 10% from 2012. There is no data from the Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration.

But the cases handled by the LCIA, ICC, SIAC and HKIAC are dwarfed by those of China International Economic and Trade 2 PDRCI PhiliPPine DisPute Resolution CenteR, inC. Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), which handled 1,256 cases in 2013, of which CIETAC Beijing administered 1,058 cases; the CIETAC Shanghai Office administered 159 cases, and the CIETAC Shenzhen Office administered 18 cases. The other 21 cases were spilt between the CIETAC South-east China Subcommission and the Tianjin Finance Centre.

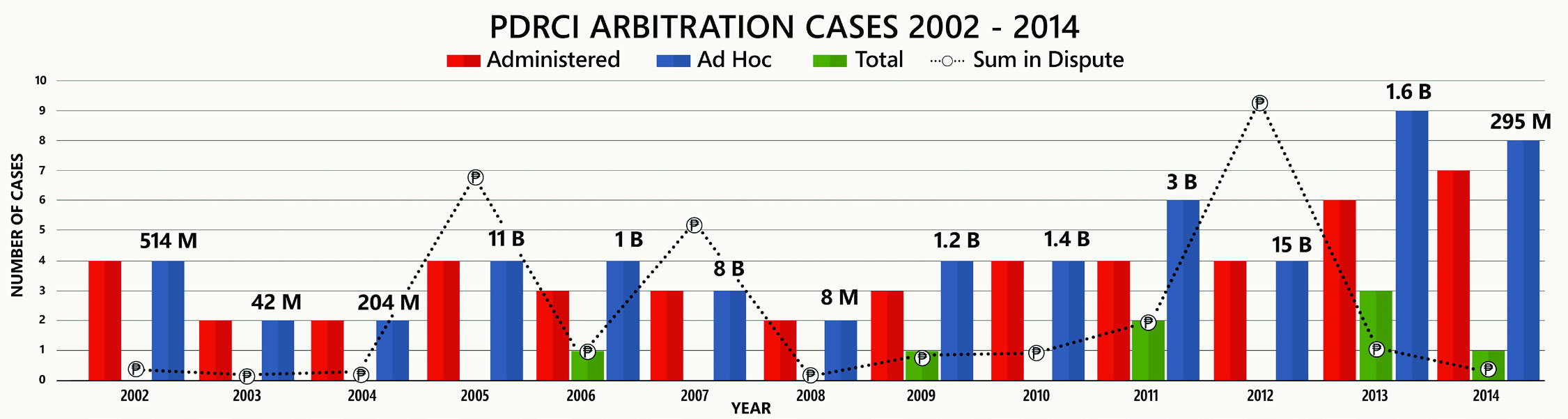

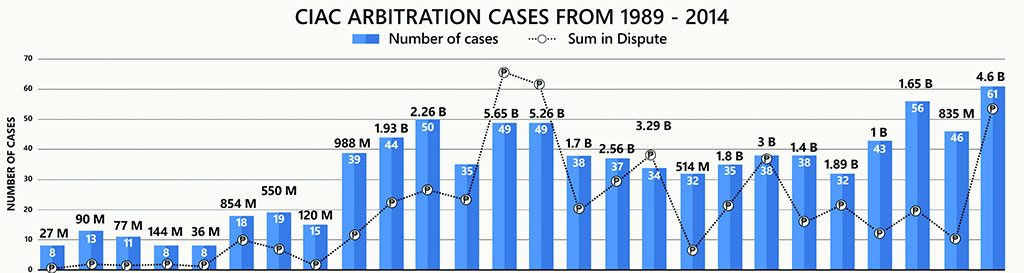

In comparison, the number of cases handled by PDRCI and the Construction Industr y Arbitration Commission (CIAC) can best be described as modest. In 2013 and 2014, PDRCI handled only nine and eight cases with total values of Php16B and Php295M, respectively. CIAC handled 46 cases in 2013 with a total value or sums in dispute (SID) of Php835. 2M, which increased to 61 cases in 2014 with a total value of Php4.6B. If we combine the cases of PDRCI and CIAC for 2014, a total of 69 cases were referred to arbitration in both institutions. There is no reliable data on ad hoc arbitration. The closest information is from the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP). According to Jerome Abella of the IBP National Office, the IBP National President received six requests for appointment of arbitrators for 2014. The IBP national office is also the venue of two ad hoc arbitrations.

What the data means

While no recent study has been done to explain these data, the author offers several observations.

● The use of commercial arbitration in the Philippines, both ad hoc and institutional, is low.

● Many of the ad hoc and institutional arbitrations handled by PDRCI involve foreign corporations.

● Local parties prefer to litigate instead of referring their disputes to arbitration. The exception is in construction arbitration, where most of the parties are either domestic corporations or Philippine residents. In construction disputes, local parties prefer to arbitrate instead of litigate.

● When local corporations agree to arbitrate, oftentimes it is because they were required by their foreign counter-parties to include an arbitration clause in their agreements. The arbitration in such cases will usually be administered abroad by a foreign arbitral institution perceived to be neutral to both parties, such as the ICC, SIAC, or HKIAC.

● Certain jurisdictions such as London, Paris, Singapore and Hong Kong are perceived to be arbitration-friendly, with procedural laws and rules that favor arbitration.

● The Philippines is not considered to be an arbitration- friendly jurisdiction, even if it was the first in Asia to have an Arbitration Law (Rep. Act No. 876) in 1953 and despite the passage of the ADR Act of 2004, its implementing rules and regulations, and the Special ADR Rules for court assistance in ADR cases. The courts, especially the Supreme Court, are perceived to be interventionist and obstructive.

● Despite a high number of units allotted to ADR in the Mandatory Continuing Legal Education or MCLE requirements for Filipino lawyers, practitioners are generally unaware of arbitration and its advantages. The PhiliPPine ADR Review | JAnuARy 2015 In many cases, lawyers are averse to arbitration and other forms of ADR because of their familiarity with and preference for litigation.

● There is a need to educate business decision-makers and their lawyers, both internal and external, of the benefits of arbitration and other forms of ADR in terms of cost, efficiency, predictability, and confidentiality. Informal arbitration already exists in the business world, especially among Filipino Chinese business people, but it is coupled with negotiation. It is not true dispute resolution.

● There is also a need to develop expertise among arbitrators on the substantive law applicable to the disputes such as mergers and acquisitions, energy, telecommunications, intellectual property, banking and finance, secured transactions, investment law, construction law, mining, and others. If we have more experts in commercial law and contracts law who are engaged as arbitrators, business decision-makers will have more confidence in the arbitration process.

● Finally, there is a need to monitor ad hoc arbitrations. For this purpose, OADR can act as a clearinghouse to receive requests or complaints in ad hoc arbitration and to assist the parties in going about the arbitration process. The OADR should also issue the schedule of ad hoc arbitrator’s fees, which is mandated in the ADR Act of 2004 and its implementing rules.