The Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) recently released the results of its survey held in September 2013 on the use of hot-tubbing of expert witnesses, hearings by videoconference, hearings by teleconference, and documents-only proceedings in international arbitration within the last five years.

The Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) recently released the results of its survey held in September 2013 on the use of hot-tubbing of expert witnesses, hearings by videoconference, hearings by teleconference, and documents-only proceedings in international arbitration within the last five years.

“Hot-tubbing” of expert witnesses is the process where experts from the same discipline, or sometimes more than one discipline, give evidence at the same time and in each other’s presence. The survey showed that 61% of them encountered an increase in the use of hot-tubbing within the last five years and over 77% agreed that hot-tubbing of expert witnesses, if used in appropriate circumstances or if properly conducted by a prepared and experienced tribunal, is an effective and viable means of saving costs and reducing timelines in arbitration proceedings.

The survey also showed that 52% of the participants did not see a notable increase in the use of videoconference, while 48% observed the opposite. Nevertheless, 65% of the participants held the view that hearings by videoconference are an effective and viable means of reducing costs and timelines. Roughly 25% of the participants were of the view that only procedural, not evidentiary, hearings should be conducted by videoconference.

Over 77% of the lawyers agreed that procedural hearings involving counsel and arbitrators from different cities or countries should be conducted by teleconference, unless there are exceptional circumstances that require otherwise. 87% of the participants advise against conducting evidentiary hearings by way of teleconference, mainly because of the advantages of being able to observe the demeanor of witnesses.

At least 87% of the participants did not encounter an increase in the frequency of documents-only proceedings. Over 90% of the participants agreed that documents-only proceedings are an effective way of saving costs and reducing timelines, but must be used only in appropriate circumstances, such as when the amount of claim is small, the issues involved are simple or straightforward, or when the main issue in dispute is legal and not factual in nature.

A total of 31 arbitration practitioners from Singapore and the region participated in the survey, which was done via e-mail. Nine participants were based in the Singapore office of a foreign firm, 17 were based in a Singapore firm, while five participants were based outside Singapore.

A short history of ADR in the Philippines

Part One of the article published in the last issue discussed the development of construction arbitration and commercial arbitration in the Philippines.

A t the University of the Philippines College of Law, Prof. Alfredo F. Tadiar was then head ..of the Office of Legal Aid (OLA), where he started a program to promote the settlement of pending court cases through mediation. He trained law students to become mediators. Prof. Tadiar later joined the faculty who trained the second batch of CIAC arbitrators.

Due to clogged dockets, the Supreme Court saw mediation as an effective means to settle pending court cases and avoid disputes from reaching the courts. Together with Prof. Tadiar, the Supreme Court developed a program called CourtAnnexed Mediation (CAM). The mediation rules were adopted and mediators were trained.

The CAM was successfully pilot-tested in certain keys cities and thereafter rolled out in various courts in the Philippines. The success rate of CAM is approximately 70%. The expectation is that the CAM program will be operational in all 1st and 2nd level courts in the country. It has also proved successful in settling appealed cases in the Court of Appeals. To my mind, Prof. Alfredo F. Tadiar is the father of CAM.

Coming from her post-graduate studies in mediation at the Harvard University, Prof. Anabelle T. Abaya was a passionate advocate of mediation— particularly out-of-court mediation. She organized the Conflict Resolution Group Foundation Inc. (CORE), which specialized in training mediators and promoting mediation.

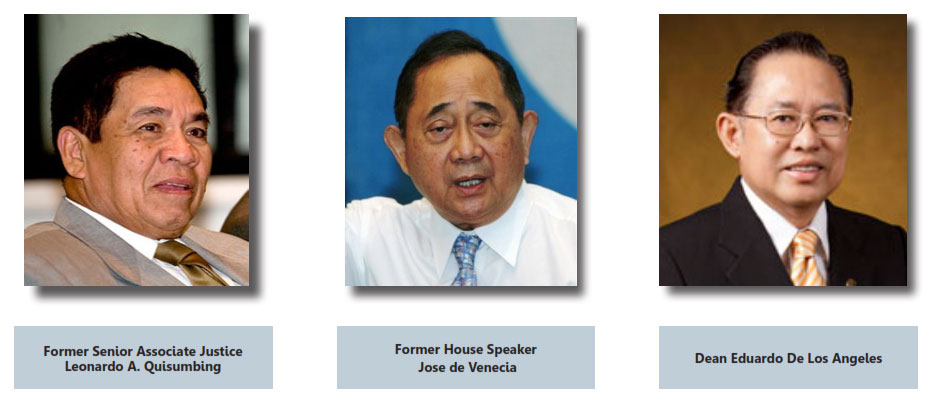

As she had the ear of then Speaker of the House of Representatives Jose De Venecia, she spearheaded the drafting and passage of a new ADR Law. She recruited, among others, Dean Parlade, Professor Mario E. Valderama and I to draft and lobby for the bill. The proposed ADR bill eventually became The ADR Act of 2004. Prof. Abaya was the principal drafter of the Chapter on Mediation. She was likewise part of the committee that drafted the Implementing Rules and Regulations, again focusing on the Chapter on Mediation. Thus, she is rightfully the mother of out-of-court mediation.

For his part, Prof. Mario E. Valderrama organized Philippine arbitrators who were accredited fellows of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators into the Philippine Institute of Arbitrators (PIArb). PIArb is an affiliate of the East Asia Branch of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. As President of PIArb, Prof. Valderama is an active lecturer on and promoter of arbitration.

In 2008 to 2009, the Supreme Court, through Senior Associate Justice Leonardo A. Quisumbing, initiated a move to adopt procedural rules of court pertaining to ADR. The procedural rules would dovetail with The ADR Act of 2004.

The members of the Committee were Justice Quisumbing as Chairman, Dean Parlade as Vice-Chairman, and Prof. Tadiar, Dean Eduardo De Los Angeles, Atty. Ismael G. Khan, Jr., Dean Jose M. Roy III, Asst. Solicitor General Rex Bernardo L. Pascual, Asst. Solicitor General Rebecca E. Khan, Atty. Patricia Tysmans-Clemente, and myself as a members.

On September 1, 2009, the Supreme Court adopted the Special Rules of Court on Alternative Dispute Resolution. The rules defined the procedure in cases where court intervention is permitted in ADR proceedings and provided order and uniformity in the way courts handle and resolve issues and incidents relating to ADR. Thus, the father of the ADR procedural rules or the Special Rules of Court on ADR is Justice Leonardo A. Quisumbing.

Except for CAM and PIArb, I was fortunate to have been involved in the drafting of substantive laws, rules of procedure, and the implementing rules and regulations pertaining to the various ADR modes. From that perspective, this is my take on the history of ADR in the Philippines.